You can’t see it or touch it, but it’s in everything you see and touch.

We're talking about hydrogen – the most abundant element in the universe – and its potential as a cornerstone of the energy transition which is generating a lot of excitement in the energy industry and beyond.

If you’re wondering why there’s so much hype about hydrogen lately, what it’s used for, and its potential to help achieve climate goals, read on.

What is hydrogen and why is it important?

Operating at scale, clean hydrogen and hydrogen-based fuels could play a central role in efforts to decarbonize the global energy system, alongside technologies like renewables and carbon capture, utilization and storage solutions.

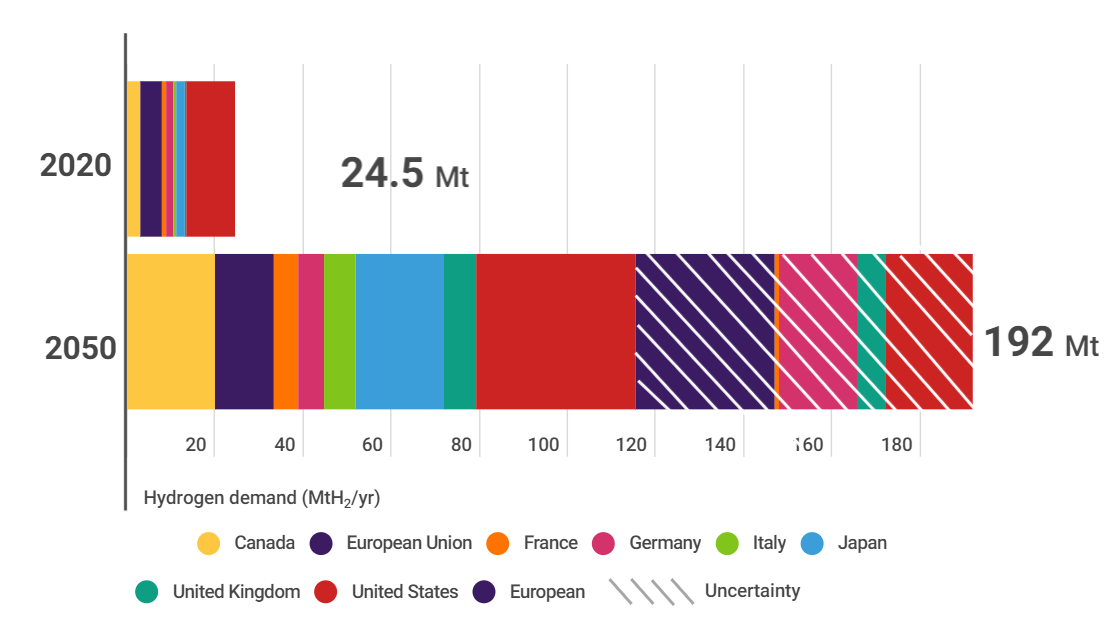

Hydrogen demand from G7 members from 2020 to 2050. Image: IRENA.

As part of the Net Zero Emissions Scenario 2021-2050, hydrogen and hydrogen-based fuels could avoid up to 60 gigatonnes of CO2 emissions by mid-century – equivalent to 6% of total cumulative emissions reductions, according to the International Energy Agency (IEA).

Uses of hydrogen

So why is there so much buzz about the benefits of hydrogen as an energy transition fuel?

One of its key advantages is that it is the perfect complement to renewables. Wind, solar and other renewables remain vital for the global energy transition, and they can be complemented by on-demand power generation when output from renewable sources cannot meet all of the electricity demand,.

Part of the reason is hydrogen’s potential to help decarbonize sectors like hard-to-abate industries, mobility and power generation.

Today, the majority of hydrogen is used by the refining and chemical industries. Demand for industrial use has tripled since 1975 and its potential as an energy transition fuel could see demand grow exponentially.

Similarly, hydrogen could help decarbonize hard-to-electrify heavy mobility sectors like shipping, railways and buses. The IEA’s Global Hydrogen Review 2022 notes positive signs of progress in this field recently, as the first fleet of trains powered by hydrogen fuel cells began operating in Germany, for example.

There is strong interest for clean hydrogen from global players, with several strategic partnerships in place within the shipping sector keen to curb its emissions in the face of ever-stricter regulatory restrictions imposed on fleet owners and operators by the International Maritime Organization (IMO). Currently, more than 100 pilot and demonstration projects using hydrogen or its derivatives to fuel shipping, are under way.

Some heavy industries are also eager to embrace the decarbonizing potential of hydrogen. A year after the first experimental projects produced clean ‘green’ steel using renewable energy, a flurry of new steel projects have been announced that will use emissions-free hydrogen in the direct reduction of iron.

The 5% increase in global hydrogen demand between 2020 and 2021 reflects an overall increase in both new and traditional applications across regions.

A clean hydrogen is a powerful tool which can support different countries’ unique needs, compliment natural endowments and interconnect regions, as reflected by 26 countries issuing national hydrogen policies. Due to hydrogens flexibility, and ability to decarbonize hard-to-abate sectors, provide energy security, and redistribute renewable energy across geographies there are 680 projects in the pipeline, with each geographical region playing a key role. For example, Europe is home to 30% of hydrogen investment, whilst North America operates 80% of the global low carbon hydrogen capacity. Meanwhile, South Korea and Japan are essential in supporting the supply chain, having produced half the global fuel cell manufacturing capacity.

The hydrogen rainbow

It’s important to note that not all types of hydrogen are created equally. Despite being a colourless gas, hydrogen is labeled in a rainbow of colours, each representing a different method of production with its own emissions footprint. These are the three main colours of hydrogen:

Grey – Hydrogen produced by combusting natural gas, which emits CO2 into the atmosphere. (This method emits less than black or brown hydrogen produced using different types of coal.)

Blue – Low-carbon hydrogen produced from combusting natural gas for steam methane reforming, in conjunction with carbon capture and storage technology removing most CO2 emissions from flue gases, which is stored securely underground. In this case, hydrogen can only be labelled “clean” if methane leakages are minimised to near zero, the carbon capture rates are high, and the carbon captured is permanently stored underground to prevent its release into the atmosphere.

Green – Emissions-free hydrogen produced using an electrolyser powered by renewable energy.

While these simple descriptions explain the different ways hydrogen is produced, there is a lack of global consensus regarding hydrogen standards, for example there is no specific carbon intensity limit for low-carbon and renewable hydrogen. Both production routes will need to achieve verifiable low-carbon intensities that move towards near zero by 2030, according to the Breakthrough Agenda Report 2022 – a collaboration between the IEA, IRENA and the UN Climate Change High-Level Champions.

The vast bulk of hydrogen in use today is generated using fossil fuels, which emits CO2 into the atmosphere and contributes to the climate crisis. In 2021, natural gas accounted for around 60% of total production with coal accounting for about 20%, the IEA notes.

Green hydrogen makes up only about 0.1% of overall hydrogen production, but this will increase as the cost of renewable energy and electrolyser technology continues to fall.

Generating a clean hydrogen future

Demand for hydrogen reached 94 million tonnes in 2021, containing energy equal to about 2.5% of global final energy consumption, up from a pre-pandemic total of 91 Mt in 2019, IEA figures show.

While most of the increase came from dirty sources, there are signs of positive change on the horizon with a spike in low-carbon hydrogen projects being planned, including several at an advanced stage.

At the same time, in the wake of the current energy crisis, governments are seen to increasingly pursue a future-proof strategy, investing in new natural gas and LNG infrastructure, which could in the future accommodate clean hydrogen.

If all current projects are brought online, by 2030, low-carbon hydrogen capacity could reach 16-24 Mt annually, with green hydrogen from electrolysers accounting for 9-14 Mt and blue hydrogen accounting for between 7-10 Mt.

However, in a sector characterized by a trinity of uncertainties about future hydrogen demand, inconsistent regulatory frameworks, and a lack of available infrastructure to transport hydrogen, just 4% of new projects are under construction or have made it to a final investment decision, the IEA Global Hydrogen Review 2022 shows.

In 2022, year-on-year annual electrolyser capacity doubled to reach 8 gigawatts.

If all the new projects announced by the industry are brought to life, this could reach 60 gigawatts annually by 2030. And if this happens alongside the planned scale-up in manufacturing capacities, the cost of electrolysers could fall by 70% by 2030, compared with 2022 prices – similar to the dramatic price falls that helped boost wind and solar power take-up.

Amid these signs of progress, there are also words of caution. Production of clean hydrogen is not growing fast enough to meet the IEA’s Net Zero Emissions by 2050 Scenario.

Urgent action is required to encourage greater investment and incentives to both scale-up supply and create demand for premium-priced low-carbon hydrogen.

This is the focus of the Accelerating Clean Hydrogen Initiative, which has been working with stakeholders across the board to enable the clean hydrogen economy in key geographies as early as 2030, mobilising public and private actors around key enabling frameworks in specific geographies.

This article was originally posted by: WEFORUM